Prof Carolyn Pedwell gave an overview of her book Revolutionary Routines at the Complexity and Management Conference, 2025. You can watch her presentation here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=niWTBSKABmM&t=12s

In her talk she covered a number of topics which privileged the every day, local and emergent interactions between humans, which is also the subject/object of our research community.

In response I re-presented some of the themes she covered from a complexity perspective, not as a form of critique, but as a way of bringing to light what it was I saw in her book when I first read it. I thought she would be a great speaker for our conference. Carolyn’s book and the perspective of perspectives we term complex responsive processes have family resemblances.

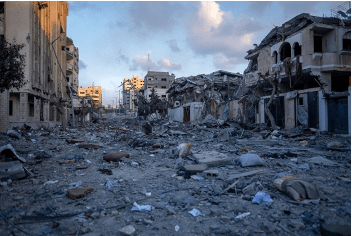

First, some context about some of the trends that we experience at the moment. which may provide some background better to understand our current times.

Norbert Elias reminds us that social progress isn’t linear, and that our increasing advances in the natural sciences and technology have not necessarily been accompanied by a similar progress in our ability to deal wisely with one another.

‘The civilization of which I speak is never completed and always endangered. It is endangered because the safeguarding of more civilised standards of behaviour and feeling in society depends upon specific conditions. One of these is the exercise of relatively stable self-discipline of the individual person. This, in turn, is linked to specific social structures’.[1]

Elias points to the link between relatively stable self-discipline of individuals and global patterns of relating, which are usually sedimented into institutions. ‘Civilised’ ways of behaving towards each other become established and publicly codified, and provide the checks and balances which constrain more authoritarian or arbitrary behaviour. If this is the case, then it’s a short step to understand why it is that when we are governed by less stable individuals they begin by undermining the very institutions such as the courts and the press, which arose to constrain more capricious ways of governing. The authoritarian claim, as Elias both witnessed and anticipated, is the paradox that the civilising institutions must be done away with in order to save civilisation:

‘….power elites, ruling classes or nations often fight in the name of their superior value, their superior civilization, with means which are diametrically opposed to the values for which they claim to stand. With their backs against the wall, the champions easily become the destroyers of civilization. They tend easily to become the barbarians.’[2]

Authoritarians gain access to power through democratic means, but then use this power to undermine democracy. But how might we understand these developments in terms of our every day encounters, about which both Carolyn’s book and the perspective of complex responsive processes has something to say?

Carolyn’s explores a pragmatic understanding of the immanent potential of change in everyday encounters and discusses popular movements aimed at greater democracy and greater solidarity, what we might consider generative ends. But she acknowledges that there is more than one revolutionary project in train at the moment, some of them aimed at the opposite. As an example of the latter, Mrs Thatcher was one among a number of politicians who also pursued policies in government with revolutionary intent for shaping the identity of British citizens, the consequences of which we still experience:

And therefore, it isn’t that I set out on economic policies; it’s that I set out really to change the approach, and changing the economics is the means of changing that approach. If you change the approach you really are after the heart and soul of the nation. Economics are the method; the object is to change the heart and soul.[3]

We have become individualised over the longer term, but the last few decades have accelerated the pace at which we come to think of ourselves as set apart from one another, the architect or our own choices, consumers rather than citizens. As the same politician observed, there is no such thing as society, only individuals and their families.

The dominant form of relating in many societies is closer to the situation Elias described in The Germans, with the civilising process gone into reverse. We experience huge inequality and fragmentation, authoritarian politics and a lack of confidence in the political process. As the German sociologist Hartmut Rosa has identified, the pace of change is so rapid that democracy seems inadequate as method of decision-making, always limping behind events. A survey commissioned by the British advocacy group Hope not Hate found that 40 per cent of British people would prefer a ‘strong and decisive leader who has the authority to override or ignore Parliament’ to a liberal democracy with regular elections and a multi-party system.

What kind of feeling states and behaviour towards one another do these attitudes imply?

In contemporary discourse we experience what cultural theorist Richard Seymour defines as a combination of apocalyptic fantasy, nationalist resentment and libidinal excess. This is not just a state of affairs, but a state of being. Seymour argues, as does Carolyn, that for global patterns of fascism to arise, it must present in everyday interactions:

‘Before fascism becomes a movement, it must circulate in everyday life, in the nascent form of everyday paranoia and victimhood, fantasies of restitution and revenge, desire for domination, the authoritarian need to be right, the capacity to humiliate, approval seeking in-group conformity and converse tendencies towards malice and social sadism. These are the ordinary fascist jouissances, or micro-fascisms, that, when given the appropriate ideological shape, announce themselves loudly in moments of crisis.’[4]

A prominent mode of relating, mobilised in particular by politicians on the right, is based on resentment, which the social anthropologist Didier Fassin considers a relational phenomenon connected to people’s sociological position:

‘It involves diffuse animosity and tends toward vindictiveness. It shifts its object of discontent from specific actors toward society at large and vulnerable groups in particular, via imaginary projections. The resentful man is not directly or indirectly exposed to oppression and domination, but he expresses discontent about a state of affairs that does not satisfy him.’[5]

Increasing inequality, erosion of social status and the degrading of public services are the breeding ground for revolutions of a regressive kind, expressed in strong feelings, particularly directed towards groups lower down in the social hierarchy, who are cast as scapegoats. So considering change in the minor key, as Carolyn encourages us to do, involves paying attention to the everyday politics of resentment and hostility that currently grips us, at least in the UK, bearing in mind that no way of relating is totalising, even if it is prominent, but will in turn call out movements of solidarity, collective identification and resistance.

Some similarities between Revolutionary Routines and complex responsive processes

What I noticed in Carolyn’s presentation are the paradoxes which are central to pragmatic thought, and to the way we interpret the complexity sciences, particularly in the form of evolutionary complex adaptive systems. A complexity response to the structure/agency question is that global patterns emerge simply and only as a result of what everyone is doing together – this is the paradox of forming and being formed which we refer to constantly. Elias formulated this as the interweaving of intentions, of which no one, and no group, is in overall control, which cause the patterns in society which constrain and enable us. Meanwhile, Mead articulates why it is that we may feel distress in the body about what is going more widely in society:

‘Every individual self within a given society of social community reflects in its organised structure the whole relational pattern of organised social behaviour which that society of community exhibits or is carrying on, and its organised structure is constituted by this pattern;’[6]

Another way of putting this, after Bourdieu, is that the body is in the social world and at the same time that the social world is in the body. Similarly, Carolyn says this in her book: ‘individual habits are not discrete or separable from institutional or environmental patterns, rather, they are always intimately intertwined.’ (p102).

The other family resemblance I noticed with our approach to complexity in Carolyn’s talk was the imminence of change. In other words, there is no reality to be acted upon, no inside and outside, but rather interactions simply produce further interaction. The pragmatists are suspicious of the dualisms of inside/outside, self/society, mind/body, and so too is SH Foulkes who informs our group work:

‘Each individual – itself an artificial, though plausible, abstraction – is centrally and basically determined, inevitably, by the world in which he lives, by the community, the group, of which he forms a part. The old juxtaposition of an inside and outside world, constitution and environment, individual and society, phantasy and reality, body and mind and so on, are untenable. They can at no stage be separated from each other, except by artificial isolation.’[7]

More orthodox organisational theory tends to take a constructivist position, choosing interventions from ‘outside’ the situation, as though an organisation is a thing to be engineered or ‘leveraged’. Assuming that change is immanent also implies a complex theory of time, what Mead refers to as the living present, and also captured by Dewey in a quotation in Carolyn’s book:

‘’Present’ activity is not a sharp narrow knife-blade in time. The present is complex, containing within itself a multitude of habits and impulses. It is enduring, a course of action, a process including memory, observation and foresight, a pressure forward, a glance backward and a look forward.’[8]

What I recognise in Carolyn’s thesis about the significance of the minor gesture is firstly the non-linearity of radical transformations of social patterning – small perturbations in habit can lead to population wide changes over time, while large scale, whole-organisation change programmes aimed at reconfiguring behaviour can lead to no change at all. Next, attention to the local, minor and current deprioritises the future, which we can hold on to more lightly. Rather, our focus should be as much on the present with its ‘multitude of habits and impulses’. Change, Carolyn argues, in non-teleological. That is to say, her theory of change goes against the common sense understanding that you can’t make progress unless you have a destination in mind and a map to get there. Instead, the emphasis is on paying attention to being blown about in the present with ‘a glance backward and a look forward’. As Carolyn says herself in the book:

‘As politics oriented towards the present, pragmatism is wary of over-investment in models of revolutionary change that promise to overthrow the entire system, not least because in a complex and shifting world, there is not singular or self-sustaining ‘system’ to overthrow.’[9]

The complexity perspective we have developed at UH is much more focused on people and what they say and do in the living present than we are in parts and whole abstractions and grand schemes for organisational change. I am reminded of a seminar I attended with Hartmut Rosa in Denmark where he doubted that we could make better sense of our current difficulties using the exact ways of thinking that have got us into the messes we find ourselves in. This, in Dewey’s terms, is simply replacing one rigidity with another. Rather, as the contemporary pragmatist Richard Rorty expressed it:

‘What (pragmatists) hope is not that the future will conform to a plan, …but rather the future will astonish and exhilarate…what they share is their principled and deliberate fuzziness.’[10]

I appreciate that fuzziness, the importance of the present moment, privileging the minor key, doesn’t go down well in a work world dependent upon metrics, KPIs and future-oriented instrumental thinking which idealises whole change.

Lastly I want to respond to Carolyn’s invitation to develop ‘shared capacities to sense the minor currents which run through major configurations’, which she argues could lead to new and generative forms of solidarity. Two major capacities that we pay attention to in the complexity research community are group mindedness and critical reflexivity.

By group mindedness I mean the decentering process that develops from sitting in an experiential group over a period of time, which anyone involved in group practice is exposed to. It involves learning to pay attention to group dynamics as a means of becoming wiser about oneself and more skillful in group participation. Experiential groups depend upon the increased capacity of its members to pay attention to what’s going on, and to notice the minor currents which emerge between people as they try to make sense of staying in relation. Foulkes, the founder of the Institute of Group Analysis, describes the process as a form of ego-training, but it also increases the capacity to sit with uncertainty and not close down the sense-making process prematurely. Group work reminds me of Sally Rooney’s latest novel Intermezzo, where she describes the demands that we place on each other thus:

‘The demands of other people do not dissolve; they only multiply. More and more complex, more difficult. Which is another way, she thinks, of saying: more life, more and more of life.’

For me, becoming more experienced in groups also increases one’s ethical capacity to widen one’s circle of concern. Even the most straightforward situation can break open into the manifold.

By critical reflexivity I mean increasing one’s capacity for problematising the taken for granted, for making the unseen seen. It is sometimes an uncertain and potentially marginalising activity as Hannah Arendt reminds us:

‘Thinking as such does society little good, much less than the thirst for knowledge, which uses thinking as an instrument for other purposes. It does not create values; it will not find out, once and for all, what the ‘good’ is, it does not confirm but rather dissolves accepted rules of conduct.’[11]

In an increasingly authoritarian and polarised world, it can take some courage to ask questions, to probe, to seek justifications, to evaluate the goods in any situation, to think about one’s own participation and the assumptions which underpin it. It can feel ‘unproductive’ when so much emphasis is placed on achieving things, and concrete, identifiable outcomes. Encouraging critical reflexivity in a group context can have an additional power, but in my view it leans towards what Carolyn asked for, creating new and generative forms of solidarity. As the German sociologist Rahel Jaeggi puts it:

‘We can find ourselves in (our actions) only if we better understand ourselves as part of a social context that equally makes possible, shapes, determines and limits our self-conceptions. A life of one’s own, then is something that emerges not in abstracting from but in appropriating a shared life.’[12]

A key insight from many of the thinkers that we draw on in the complexity research community is the paradox that individuation, a fuller sense of agency, is achieved in and through a group. It is the substrate through which individuation takes place. In recognising the interdependence of our lives together, and becoming more skillful at noticing emerging trends and difference between us, we may become more fully our selves in our shared lives with others.

[1] Norbert Elias -The Germans (1997) p173

[2] Norbert Elias, The Germans (1997) p359

[3] Interview with Ronald Butt in The Times, 3/5/1981.

[4] Richard Seymour, (2024): Disaster Nationalism: the downfall of liberal civilisation, p206.

[5] Fassin, (2013) On Resentment and Ressentiment: The Politics and Ethics of Moral Emotions, Current Anthropology, Volume 54, Number3, p260.

[6] GH Mead, (1934) Mind, Self and Society: 221-222.

[7] Foulkes, S.H. (1948) Introduction to Group Analytic Psychotherapy, Karnac: p10.

[8] Dewey, J. [1922] (2012) Human Nature and Conduct, p110.

[9] Pedwell, C. (2021) Revolutionary Routines, p53.

[10] Rorty, R. (1999) Philosophy and Social Hope, p 24.

[11] Arendt, H. (2003) Thinking and Moral Considerations, in Responsibility and Judgement: p188.

[12] Jaeggi, R (2016), Alienation, p218